4D-STEM of disordered materials

Disordered materials lack long-range order (>~20 Å). However, they will have significant short-range order (between the nearest neighbor atoms) and medium-range order (~3-20Å). Using a probe with a diameter in the size at which the disordered material has order allows for a sensitive analysis of atomic angular arrangements. Such small probes cannot be obtained with X-rays, while this is possible with electrons. Hence, studies with 4D-STEM of disordered materials give the opportunity to investigate local atomic structures of disordered materials, which are otherwise hard to access.

Disordered carbons

The property of carbon to occur in three different hybridization states leads to versatile structures of carbon materials. There are not only >1000 crystalline carbon allotropes but also a large variety of disordered carbons. These disordered carbons often show outstanding properties, for example as electrode materials for batteries or electrocatalysis, for gas absorption and separation, and water purification. However, often their atomic structure is not well-described.

In our group we try to develop methods to describe the atomic structure of disordered carbons better. Thereby, features like curvature, and defects in the extended-range order (~2-10Å) within and in between graphite-like layers are of high interest, as they will directly affect the properties of the material and can be challenging to characterize. For that we utilize tools, like 4D-STEM and PADF, to try to tune them so that they are more sensitive for the analysis of the important features in disordered carbons.

Revealing the Structure of Polyoxometalate Clusters (RESPOM)

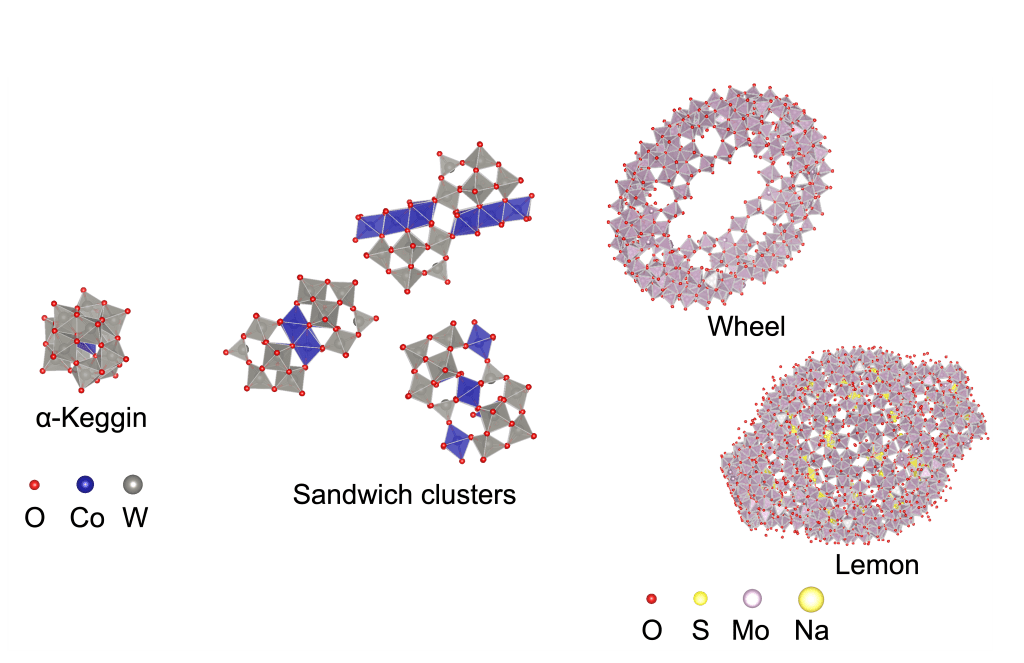

Polyoxometalates (POMs) are inorganic metal-oxo clusters composed of early transition metals (typically Mo, W, or V) arranged in networks of corner- or edge-sharing MO₆ octahedra. Their structural diversity, from compact Keggin clusters to sandwich-type POMs and large “wheel” or “lemon” clusters, gives rise to promising applications within catalysis, sensing, energy storage, and nanomedicine.

Within the DISORDER group, the RESPOM project focuses on revealing how POMs are structured in their non-crystalline states where they are most often used: in solution, as amorphous solids, or immobilized on supports. By combining advanced electron microscopy techniques (4D-STEM, PADF, cryo-EM and SPA), we aim to clarify how the POM structure relates to function, specifically electrocatalysis, enabling better design of next-generation POM-based materials.

Multi-scale analysis

Many functional materials derive their unique properties from structural features across multiple length scales. Catalysts are a prime example: their performance depends on both elemental composition and surface structure, which govern the chemical reactions they facilitate. At the nanoscale, catalysts often appear as nanoparticles, visible in transmission electron microscopy, providing high surface area and active sites.

These nanoparticles are typically dispersed on a support material, where micro- and macroscopic porosity plays a critical role in transporting reactants and products. On the largest scale, this multiphase catalytic material may be used as a powder or shaped into pellets through pressing or extrusion, making it suitable for industrial reactors.

To truly optimize a catalyst, it is essential to characterize its structure at all relevant scales – from atomic arrangements to reactor-sized components. Our research focuses on developing and applying advanced techniques to bridge these scales, enabling a comprehensive understanding of material performance.

New software tools

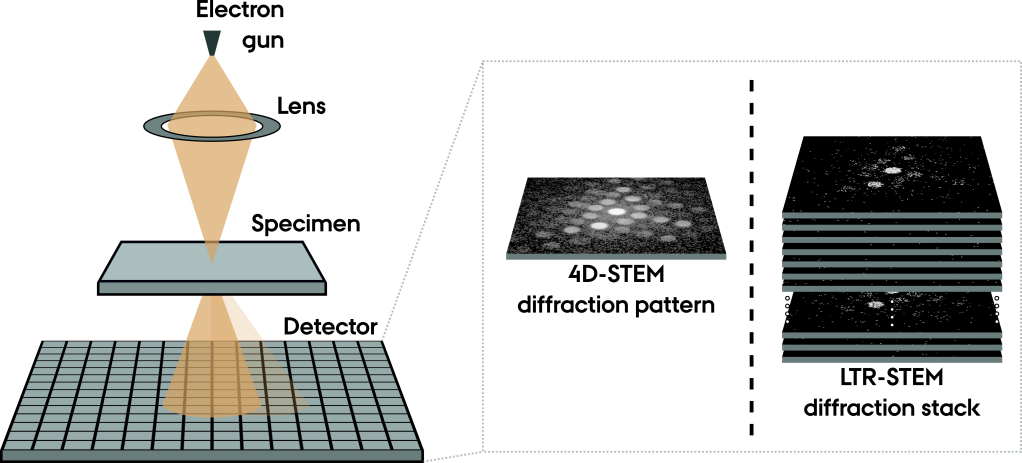

Electron microscopy provides exceptionally detailed insights into very small sample volumes, making it one of the most powerful tools for materials characterization. Modern microscopes are highly versatile and support a wide range of advanced techniques. For example, EDX delivers elemental composition, while 4D-STEM captures spatially resolved electron diffraction, revealing crucial crystallographic information.

However, these techniques often generate complex, data-rich datasets that require sophisticated analysis. The sheer volume and complexity of the data typically limit studies to extremely small regions – sometimes so small that the results lack statistical significance.

At the DISORDER group, we develop innovative software solutions to overcome these challenges. Our tools aim to:

- Streamline advanced data analysis, making it faster and more accessible.

- Enable analysis of larger sample volumes, improving statistical reliability.

- Unlock hidden correlations within electron microscopy datasets – such as links between elemental composition, defects, particle size, and structure.

By pushing the boundaries of data processing, we strive to extract the full potential of information-rich microscopy techniques and accelerate discoveries in materials science.

Dynamics in disorder with 4D-STEM

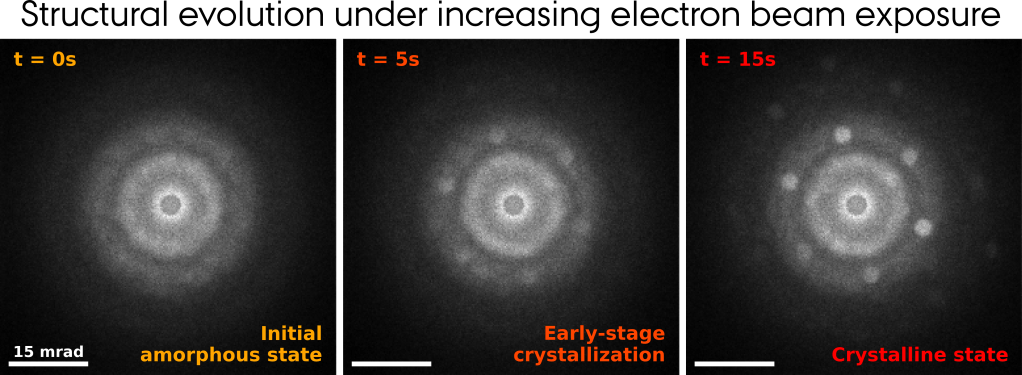

Understanding structural transformations is essential for controlling material functionality, particularly at the nanoscale where disorder, heterogeneity, and fluctuations often dominate behavior. Many technologically relevant materials, such as amorphous, nanocrystalline, and defect-rich systems, do not evolve through simple, well-defined pathways, making their dynamics difficult to capture with conventional static characterization techniques.

To study the fluctuations in disordered materials, or how they respond to externally applied conditions, the locally time-resolved STEM (LTR-STEM) technique was conceptualized. By extending 4D-STEM with time-resolved acquisition strategies, diffraction stacks are acquired at each beam dwell position, enabling observation of structural dynamics as they unfold, even in systems lacking long-range order.

This approach provides access to local, transient rearrangements and collective responses that underpin phase transformations, relaxation processes, and beam-matter interactions in disordered materials. In some cases, LTR-STEM is used to probe structural fluctuations and relaxation dynamics as a function of time. In others, the energy supplied by the electron beam drives the system across a phase transition, leading to crystallization from an initially disordered state. Using this framework, we study beam-induced crystallization processes in materials such as zirconium oxides, ferrovanadium, and related disordered systems.